Tag: science’

Edible Water Balloons (and popping boba)

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Sodium alginate (Say it like you say algae!) is a substance found in the cell walls of brown algae, including seaweeds and kelp. Its rubbery, gel-like consistency may be important for the flexibility of seaweed, which gets tossed around on ocean waves.

Edible Water Balloons- KitchenPantryScientist.com

Here on dry land, you can use sodium alginate to make edible balloon-like blobs that are liquid in the middle. We can thank scientists for this delicious project, since they discovered that a chemical reaction between sodium alginate and calcium causes the alginate to polymerize, or form a gel. In this experiment, the gel forms on the outside of a sodium alginate blob, where the chemical reaction is taking place. The inside of the blob remains liquid!

No heat is required for this experiment, making it safe and fun for all ages!

Sodium alginate and calcium lactate can be tricky to find at the grocery store, so you’ll probably have to order them online. But they’re not very expensive, and you’ll have lots of fun playing with them!

You’ll need:

-a blender or hand blender (parental supervision required for small children)

-1/2 tsp sodium alginate

-2 tsp calcium lactate

-flavored drink drops, like Kool-Aid or Tang (optional)

-water

-a spoon

-squeeze bottle or syringe for popping boba*

You can make these with juice, but if there is any calcium in the juice, you may end up with foam in your blender, since it may start to polymerize the sodium alginate when you blend it in.

- Add 1 and 1/2 cup water (or calcium-free juice) to the blender.

- To the water, add 1/2 tsp. sodium alginate.

- Blend for about a minute, and let rest for 15 or 20 minutes, or until the bubbles are gone.

- If you want to add flavor, divide the sodium alginate solution into small containers and stir in the flavor, like a squirt of Kool-Aid liquid.

Add liquid drink drops to add flavor and color (KitchenPantryScientist.com)

- Add 4 cups of water to a clean, clear glass bowl or container.

- To the water, add 2 tsp. calcium lactate and mix until completely dissolved. This is your calcium lactate “bath.”

- To make edible water balloons, fill a spoon, like a tablespoon, with the sodium alginate solution, and slowly lower it down into the calcium lactate bath. You’ll see a gel begin to form. Gently turn the spoon so the sodium alginate falls off the spoon and into the calcium lactate.

Gently turn the spoon upside down.

- After about 30 seconds, you’ll be able to see a pale blob in the water. Leave it there for three or four minutes. You can make several edible balloons at once.

After a few minutes, you’ll see a pale blob.

- When the blobs are ready, use a spoon to carefully remove them from the bath and put them in a clean bowl of water for a few seconds to rinse them off.

Rinse balloons off in water.

- Put your edible balloons on a plate and taste them. What do you think?

- *To make popping boba, add the fruit-flavored sodium alginate to a squeeze bottle or syringe. Drip the flavored sodium alginate into the calcium lactate as fairly large drops. It may take some practice to get uniform drops of the size you desire. When they’re solid enough to remove from the calcium lactate, rinse them gently and add them to your favorite drink. A small sieve works well for rinsing.

Now that you know how to polymerize sodium alginate with calcium, what else could you try? Can you make a foam in the blender? Can you make gummy worms in the bath using the rest of your sodium alginate solution? Can you invent something entirely new??? Try it!

Thank you to Andrew Schloss’s book Amazing (Mostly) Edible Science for the experiment inspiration! Adding the Kool-Aid and Tang drops to add a little flavor and color was our idea! (This blog post was first published on KitchenPantryScientist.com on May 3rd, 2016 and revised to add popping boba July 24th, 2018.)

Summer Food Science: Sorbet (No ice cream freezer needed!)

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Take your summer food game up a notch using… science! Sorbet recipe below. Vinaigrette recipe is in the post below this one.

&

Simple Freezer Strawberry Sorbet (adapted from Epicurious.com)

30 minutes hands-on prep time, 8 hours start to finish

*Parental supervision required for boiling sugar syrup

You’ll need:

a shallow dish

1 quart strawberries

1/3 cup lemon juice

1/3 cup orange juice

1 cup sugar

2 cups water

What to do:

- Make a sugar syrup by bringing 1 cup sugar and 2 cups water to a boil in a heavy sauce pan. Boil for 5 minutes.

- Puree strawberries in a blender or food processor until smooth.

- Add strawberries, lemon juice and orange juice to the sugar syrup.

- Pour mixture into a shallow dish and cool for 2 hours in the refrigerator.

- Put the chilled sorbet mix in the freezer for 6 hours, stirring every hour.

- Enjoy your sorbet!

The Science Behind the Fun:

In sorbet, sugar acts as an antifreeze agent, physically getting in the way of ice crystal formation to keep crystals small, so that you don’t end up with one big chunk of ice. Pre-chilling the mixture before freezing it allows it to freeze faster, which also encourages smaller crystals to form.

The Science of Emulsions: Vinaigrette and Mayonnaise

- by KitchenPantryScientist

“When I wasn’t at school, I was experimenting at home, and became a bit of a Mad Scientist. I did hours of research on mayonnaise, for instance, and although no one seemed to care about it, I thought it was utterly fascinating. When the weather turned cold, the mayo suddenly became a terrible struggle, because the emulsion kept separating, and it wouldn’t behave when there was a change in the olive oil or the room temperature. I finally got the upper hand by going back to the beginning of the process, studying each step scientifically, and writing it all down. By the end of my research, I believe, I had written more on the subject of mayonnaise than anyone in history. I made so much mayonnaise that Paul and I could hardly bear to eat it anymore, and I took to dumping my test batches down the toilet. What a shame. But in this way I had finally discovered a foolproof recipe, which was a glory.” Julia Child, from My Life in France

Julia’s secret for fool-proof mayo? Beat the mixture over a bowl of hot water to get the oil and eggs to form an emulsion, which is a mixture of two thing which are normally immiscible, like water and oil. In an emulsion, a bunch of one type of molecule will actually surround individuals or small groups of the other type of molecule (think ring-around the rosy with one or two people in the middle who would rather not be there.)

When you’re trying to make an emulsion, it also helps to add a mediator called a surfactant to get between and interact with the immiscible molecules to stabilize the mixture. In a vinaigrette prepared using oil, mustard and vinegar, the proteins in the mustard act as surfactants.

To make delicious vinaigrette:

- Using a fork or wire whisk, mix together: 1 Tbsp. vinegar and 1 Tbsp. mustard.

- Add 3 Tbsp. oil (olive, vegetable or your favorite), drop-by-drop, whisking until you see an emulsion form! You can tell when an emulsion begins to form, because the mixture will start to look lighter-colored and thicker as the molecules are rearranged and reflect light differently!

Try some variations on these kitchen experiments. Does it work better to use a cold egg, room temperature egg, or warm egg? What happens if you try to make mayo by setting your mixing bowl in a bowl of ICE water? Do you get an emulsion?

Can you see the difference between batches of vinaigrette? One was whipped over a bowl of ice water and the other over warm water.

When whipping up mayonnaise, adding a little water to the eggs before adding the oil helps make some of the proteins in the eggs more available to act as surfactants. Of course, adding a little mustard helps too and tastes great!

Here’s the New York Times recipe we used to make mayonnaise:

- 1 large egg yolk, at room temperature

- 2 teaspoons lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

- 1/4 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1 teaspoon cold water

- 3/4 cup neutral oil such as safflower or canola

- In a medium bowl, whisk together the egg yolk, lemon juice, mustard, salt and 1 teaspoon cold water until frothy. Whisking constantly, slowly dribble in the oil until mayonnaise is thick and oil is incorporated. When the mayonnaise emulsifies and starts to thicken, you can add the oil in a thin stream, instead of drop by drop.

*Remember that a bacteria called Salmonella enteriditis can lurk in raw eggs and make you sick, so it’s better to use pasteurized eggs for recipes like mayonnaise, where you don’t cook the eggs.

As Julia Child would say, “Bon Appetit!”

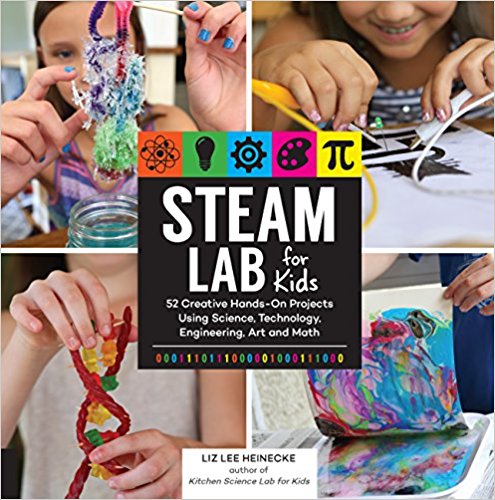

STEAM Lab for Kids: hot glue casting, candy molecules and tesselations

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Looking for fun, creative summer projects? I showed off some projects from STEAM Lab for Kids this morning on WCCO MidMorning!

CD Bots from “STEAM Lab for Kids”

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Robots took over the driveway last summer when we were photographing my new book “STEAM Lab for Kids: 52 Creative Hands-On Projects for Exploring Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math”

With a few supplies from your junk drawer and a few inexpensive tech supplies available online, kids can easily make their own CD Bots! Grab a copy of “STEAM Lab for Kids” for easy instructions, or figure out how to do it yourself by attaching a toy motor (connected to a battery) to a CD with toothbrushes glued to the bottom!

Have fun!

Balloon Rockets from “STEAM Lab for Kids”

- by KitchenPantryScientist

I took some behind-the-scenes video when we were photographing my new book “STEAM Lab for Kids” last summer. Here’s a fun engineering project from the book! #summer #fun #balloon #rockets #STEAM #STEM

Try it!

Rainbow Science

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day! Yesterday, I demonstrated some fun rainbow science on The Jason Show. Click here to watch!

As part of the segment, I featured the “Rainbow Slime” experiment from my new book, “STEAM Lab for Kids,” which you can order from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or your favorite online retailer. Here’s a sneak-peek at a few photos from the book.

Rainbow Slime from “STEAM Lab for Kids” by Liz Lee Heinecke

Rainbow Slime from “STEAM Lab for Kids” by Liz Lee Heinecke

Rainbow Slime from “STEAM Lab for Kids” by Liz Lee Heinecke

Women’s History Month: Rachel Carson

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Happy #womenshistory month! If you don’t know who Rachel Carson is, you should! Share her story with your kids and who knows? Maybe they’ll be the next Rachel Carson! (I included environmental science project ideas in the video.)

Rainbow Icicles -Winter Science for Kids

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Grab your coat and head outside to try this fun winter science project!

Rainbow Ice (kitchenpantryscientist.com)

You’ll need:

A large plastic zipper bag

Cotton kitchen twine

a toothpick or wooden skewer

ice-cold water

food coloring

a spray bottle

a squeeze bottle or syringe (optional, but helpful)

a very cold day (below 10 degrees F works best, but you can try it on any day when it’s below freezing)

Note: This experiment takes lots of playing around and results will vary depending on how cold it is outside. Remind your kids (and yourself) to be patient and try it on a colder day if it doesn’t work the first time around! If the bag leaks too quickly, try making one with smaller holes around the string.

Rainbow Ice (kitchenpantryscientist.com)

What to do:

- Use a toothpick or skewer to poke 3 small holes in the bottom of a zipper plastic bag. Make one in the middle and one on each end.

- Cut three long (3 feet or so) pieces of kitchen twine and knot them at one end.

- Carefully thread the twine through the holes in the bag so that the knots are inside the bag to keep the strings from falling through. Try to keep the holes from getting too big, since the bag will be filled with water and you’ll want it to drip out very slowly around the string.

Rainbow Ice (kitchenpantryscientist.com)

4. Attach two more pieces of twine to each top corner of the bag (above the zipper) to use for hanging the bag

5. Go outside and hang the bag from a low tree branch or railing.

6. Tie each of the three strings to something on the ground, like a rock, piece of wood, or the handle of an empty milk carton filled with water to weight it down. Arrange the objects so that the strings loosely radiate out at around a 45 degree angle. (See photo)

7. Add food coloring to some ice-cold water in a pitcher.

8. Fill the spray bottle with ice-cold water.

9. Add the cold colorful water to the zipper bag hanging outside. Zip the top of the back to slow the rate of leaking.

10. Immediately spray the strings with water to guide the leaking water down the strings.

10. Wait for the water on the strings to freeze. Use your syringe to add a little bit more water to the strings (same color) and wait for them to freeze again. Repeat until you have a nice layer of ice/icicles.

11. Refill the bag, using a different color of ice-cold water. Spray the strings lightly again. Repeat step 11.

12. Add layers of color to the icicles until you’re happy with the way they look!

Rainbow Ice (kitchenpantryscientist.com)

The science behind the fun:

Icicles form when dripping water starts to freeze. Scientists have discovered that the tips of icicles are the coldest part, so that water moving down icicles freezes onto the ends, forming the long spikes you’ve seen if you live in a cold climate. When you add different colors of water to icicles in sequence, the color you add last will freeze onto the tip of the ice.

Here’s a cool article on icicle science by an expert, and another great article on “Why Icicles Look the Way They Do.”

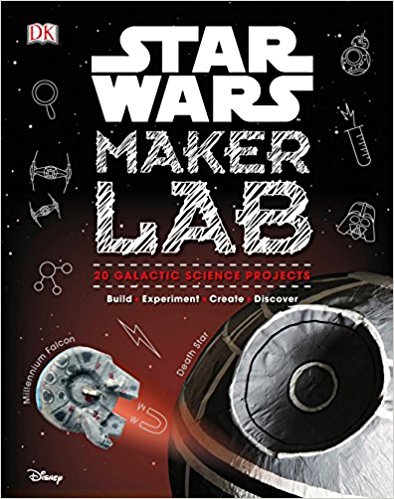

You’ll find more fun ice science experiments in my book “Outdoor Science Lab for Kids” and in my upcoming books “STEAM Lab for Kids” (Quarry Books April 2018) and “Star Wars Maker Lab” (DK- July 2018)

Mirror Image Plant Prints

- by KitchenPantryScientist

Yesterday on Twin Cities Live, I demonstrated some fun botanical science projects for learners of all ages, including Vegetable Vampires and Leaf Chromatography.

This fun art/science project lets you transfer plant pigments to cloth, creating beautiful prints of your favorite leaves and flowers. It’s especially great for fall, when there are so many colorful leaves around.

Mirror Image Plant Prints- kitchenpantryscientist.com

You’ll need:

-Fresh leaves and flowers (Dry leaves won’t work.)

-A hard, smooth pounding surface, like a wooden cutting board or carving board

-Wax paper or plastic wrap

-Mallets or hammers

-Untextured cotton cloth, like a dishtowel. Heavy cloth works better than very thin cloth.

-*Alum and baking soda to treat cloth (This is optional. I don’t pre-treat my fabric, but the treatment step will help bond and preserve color, if you want to frame your prints. You can also buy fabric that’s pre-treated for dyeing.)

Mirror Image Plant Prints- kitchenpantryscientist.com

Safety tips: Protective eye wear is recommended. Young children should be supervised when using mallets and hammers.

What to do:

*If treating cloth: The day before you do the project, add 2 quarts water to a large pot. Add 1 Tb alum and 1 tsp baking soda to the water. Add the cotton and bring to a boil. Simmer for 2 hours, turn off heat and soak for at least two hours. Let fabric dry.

The next steps are the same, whether you’re using an untreated piece of cotton or treated cloth.

- Take a walk to collect colorful leaves and flowers. Choose plants that can be flattened. Flowers with huge centers, like coneflowers don’t work as well, but petals may be removed and pounded.

- Cover the pounding surface with waxed paper or plastic wrap.

- Cut a piece of cloth that will fit on the pounding surface when folded in half. Iron the fold.

- Open the cloth and lay it on the pounding surface. (See image above)

- Arrange leaves and flowers on the cloth.

Mirror Image Plant Prints- kitchenpantryscientist.com

- Fold the cloth over the plants and pound it with the hammer or mallet. If you’re using a hammer, pound more gently.

- Pound until you can see the forms of the leaves through the fabric. As the pigment leaks through, you’ll see the outlines of what you’re smashing. Hint: Hammers work better than mallets for fall leaves. For juicy leaves and flowers, use a mallet or hammer gently.

Mirror Image Plant Prints- kitchenpantryscientist.com

- When you’re finished pounding, unfold the fabric to reveal the print you created. Remove the leaves and petals.

Mirror Image Plant Prints- kitchenpantryscientist.com

- Label the image with plant names, enhance it with paint or markers, or leave nature’s design to speak for itself.

The Science Behind the Fun:

Pigments are compounds that give things color, and many of them are found in nature. Flowers, leave, fruits and vegetables are full of brilliant pigments. In this experiment, we transfer plant pigments to cloth by bursting plant cells using pressure from a hammer or mallet.

The green pigment found in leaves is called chlorophyll. In the fall, many trees stop making chlorophyll, and the red, yellow and orange pigments inside the leaves become visible.

Although you create a mirror image of leaves and flowers, you’ll notice that the color may be more intense on one side of the print. A waxy covering called a cuticle covers leaves, and is sometimes thicker on the top than on the underside of the leaf. It may affect the transfer of pigment to the cloth, making it easy to see structures like veins on the leaf print.

Enrichment:

What parts of the leaf can you identify in the print you created?